On the morning of April 26, 1607 the

Jamestown Settlers arrived at Cape Henry.

The English came with no thoughts of enslaving the indigenous population or transporting African slaves as was being practiced by the Spanish at the time. For the first decade the mortality rate of the English settlers was high, but the Virginia Company of London kept sending more settlers with false promises of a wonderful life in Virginia. As costs mounted, in 1618 the Company began the practice of transporting indentured servants to subsidize their costs. White English people would work for a period of time before being given their freedom. One of the first to take advantage of this in 1621 was the seventh son of an Anglican minister, Adam Thoroughgood.

Slave Ships Arrive at Old Point Comfort

1619 with the First

African Slaves in Virginia

Several weeks before arriving at Point Comfort, the Treasurer and White Lion, English privateer ships, intercepted Portuguese slave ship, the San Juan Bautista, carrying Angolan slaves, sailing from Africa to Mexico. The English climbed aboard the Bautista, hoping to find a bounty of gold. Instead, they found African Angolan slaves, victims of the tragic Transatlantic Slave Trade. They took some of the slaves, splitting them between the White Lion and the Treasurer. They took the young, healthiest captives. Sir George Yeardley (1587-1627), the father of Sarah Thoroughgood-Gookin-Yeardley’s third husband, was sent to Jamestown to be the new governor. Three weeks later, in late August 1619 the English ship White Lion arrived at Point Comfort where they sold African slaves to the settlers in exchange for supplies, with Yeardley purchasing 15. The English pirate ship Treasurer was next to arrive four days later with 28 to 30 African slaves and sold only 5, now 20 in all. By 1860 there would be nearly 500,000 Virginia slaves, the nation's highest.

At Point Comfort, they were split up, with the majority of the Angolans being acquired by wealthy and well-connected English planters. They were deemed indentured servants since Virginia had no clear-cut laws sanctioning slavery. When they acquired release, if at all from their indenture, a few prospered. Known slaves coming on the Treasurer were Angelo (Angela), and Anthony and Isabella who had the first black child born in the American colonies. He was named William Tucker after their parents' master William Tucker. Baby William became the first African slave to be baptized in the American colonies on January 3rd, 1624. Later, other arrivals at Point Comfort were Anthony Johnson (1621) and Mary (1622). Within two years Anthony completed his indenture, married Mary and later acquired land by importing slaves to Virginia. On February 16, 1623, a census was taken in the colony, and African blacks included Anthony, William, John, Anthony, Angelo (Angela), John, Edward, Peter, Anthony, Frances, Margaret, Anthony and Isabella.

During these first fifty years a few blacks were able to acquire land, build their own homes, testify in court, vote, work and live among white settlers on an equal bases. Life started to change beginning in 1670 with a series of Slave Laws placing severe restrictions on their movements and conduct. In 1705 all Africans were stripped of their rights. In less than one century, the promise of freedom faded from memory, and the long night of slavery began.

John Punch – First Virginia Slave

The transformation of the social status of

African, from indentures to slaves happened gradually. The first was

in 1640 when a Virginia court sentenced African indentured servant John Punch

to slavery after he attempted to flee his service. The two whites with whom he

fled were sentenced only to an additional indenture service year. This marked

the first legal sanctioning of slavery in the English colonies and was one of

the first legal distinctions made between the English and Africans. As

time progressed the fact that African-Americans could not read or write made

court decisions harder on them.

Large Increase of Slavery after

Enactment of the 1670 Slave Law

Enactment of the 1670 Slave Law

Beginning in the 1660s the flow of English indentured

servants began to dry up and fell off dramatically in the early 1680s, forcing

planters to rely more heavily on slaves. The switch to slaves was even made

easier with a 1670 “slave law” stipulating that all Africans brought in by sea

after 1670 had to be slaves for life. Virginia farmers and planters preferred a

slave for life over a specified indenture period. The stage was now set for an

explosion of slaves with the eighteenth-century accounting for eighty percent

of all slaves brought to Virginia.

In 1687 a court recorded a Lynnhaven Parish trail for the

act of fornication between a white woman Mary Williamson and a black man

William. Mary was fined five hundred pounds of tobacco. The court records

described William’s punishment stating he “hath arrogantly behave himself in

Lynnhaven Church in the face of the Congregation. It is therefore ordered that

the Sheriff take the said William into his custody and give him thirty lashes

on his bare back.” This type of punishment persisted right up through the

nineteenth century when one of the first gruesome photos in April 1863 shows

the scars of a slave named Peter.

A 1690s Slave Sale

With the increase of slaves, their lives worsened. Most

slaves were sentenced to a lifetime of hard labor at the lash of the whip. Families were separated, never to be seen

again.

In 1730 Virginia

Governor Gooch told the Bishop of London that some of the blame for slave

unrest fell on cruel masters who "use their Negroes no better than

their Cattle.

The introduction of sugar, which become known as “White Gold,” changed the pre-industrial New World. Growing from little more than an exotic spice to a major export, it not only became responsible for the financing of the Virginia Colony but the 240-year long institution of southern slavery. Before the end of the eighteenth-century sugar from the West Indies and Brazil was the single major New World business. But this all changed when the Louisiana Territory became the first to begin granulating the sugar crystals. Along with rich soil, all that was needed were slaves to harvest the sugar-cane and work under dangerous conditions in sugar mills. By escalating the import of slaves from Africa, Louisiana quickly became the second-richest territory in per capital wealth.

The enslaved population in America climbed quickly as Europeans developed a craving for sugar products. In three centuries more than fifteen million African men, women, and children were forcibly brought to the New World by the Spanish, Portuguese, French, Dutch and British. Another estimated two million did not make it, dying on over-crowded and inhuman slave ships, victims of the Middle Passage, the second of three triangular commercial ventures. Ships from Europe traded manufactured goods for humans in Africa, as warlords and kings were willing to capture and sell members of other tribes.

Aside from Louisiana leading the colonies in deaths from harsh working conditions, the lives of Blacks during the Middle Passage became one of the largest genocides in history. Ironically, the demand for white gold was responsible for the demand for black slaves.

Tobacco in the eighteenth century became competitive in Virginia when John Rolfe’s “sweet” tobacco hit European Markets. Later in the nineteenth century the act “Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of 1807” saw an upturn in profits for Virginia plantation owners as they made large profits selling their slaves to sugar and cotton plantations in the deep south. But nothing in colonial times would match the economy of Louisiana’s white gold.

White Gold Fueled Slavery

The enslaved population in America climbed quickly as Europeans developed a craving for sugar products. In three centuries more than fifteen million African men, women, and children were forcibly brought to the New World by the Spanish, Portuguese, French, Dutch and British. Another estimated two million did not make it, dying on over-crowded and inhuman slave ships, victims of the Middle Passage, the second of three triangular commercial ventures. Ships from Europe traded manufactured goods for humans in Africa, as warlords and kings were willing to capture and sell members of other tribes.

Aside from Louisiana leading the colonies in deaths from harsh working conditions, the lives of Blacks during the Middle Passage became one of the largest genocides in history. Ironically, the demand for white gold was responsible for the demand for black slaves.

Tobacco in the eighteenth century became competitive in Virginia when John Rolfe’s “sweet” tobacco hit European Markets. Later in the nineteenth century the act “Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of 1807” saw an upturn in profits for Virginia plantation owners as they made large profits selling their slaves to sugar and cotton plantations in the deep south. But nothing in colonial times would match the economy of Louisiana’s white gold.

March 25, the International Day of Remembrance

of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

The Ark of Return, the Permanent Memorial to Honor the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade, located at the Visitors' Plaza of UN Headquarters in New York.

Mostly during the eighteenth century African men, women, and children were forcibly brought to the New World by the

Spanish, Portuguese, French, Dutch and British, more than 15 million in a 400 span. Another estimated two million did not make

it, dying on over-crowded and inhuman slave ships. They were the victims of the tragic transatlantic slave trade, one of the

darkest chapters in human history. Every year on March 25, the International

Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

offers the opportunity to honor and remember those who suffered and died at the

hands of the brutal slavery system. The International Day also aims to raise

awareness about the dangers of racism and prejudice today. In order to more

permanently honor the victims, the Ark of Return memorial was unveiled on March

25, 2015. The winning design by Rodney Leon, an American architect of Haitian

descent, was selected through an international competition and announced in

September 2013.

The Revolutionary War (1775-1783) gave slaves their first

chance at freedom. On November 7, 1775 the royal governor of Virginia, Lord

Dunmore, issued a proclamation freeing all slaves who would join his Majesty's

Troops. Many fled from their masters and joined Dunmore. Five Thoroughgood

names were listed on Lord Dunmore's African-American register, a show of

respect for their slave owners. After the war all of them had to return to

their slave owners once again with nothing to look forward to except an early

death.

James Armistead Lafayette (1748 or 1760 - 1830 or 1832)

A better fate befell James Armistead Lafayette, enslaved under William

Armistead of Virginia. William released James to serve the Continental Army

during the American Revolutionary War under the Marquis de Lafayette. As a

double agent during the run-up to the 1781 Battle of Yorktown, James was

accepted into the British fold, posing as a run-away slave. He fed British

General Cornwallis false information about the Americans while disclosing very

accurate and detailed accounts to the Americans, instrumental in helping

General Washington defeat the British at Yorktown. In 1787, through the support

of his master William, the Virginia Assembly granted James his freedom. Along

with his family, James went on to became a successful farmer.

18th Century Slaves Working in the Fields of Lynnhaven Parish

Sometimes Alongside their Master

By the close of the eighteenth-century Virginia had the largest slave population of all the states, with almost forty-five percent of its households owning slaves. Slaves built, or helped build, Pembroke Manor, Ferry Plantation, Old Comfort, and Fairfield; and most likely other homes and churches. Following are records of Lynnhaven Parish Church members that had slaves.

The Adam Keeling

House

Thomas Keeling (1608 - 1664) was one of Adam

Thoroughgood’s 105 indentured servants.

After working off his indenture, Thomas I became a plantation owner from

lands earned at the end of his indenture. His grandson Thomas II is generally

acknowledged as the one responsible for building the Adam Keeling House in the

late seventeenth century. When Thomas II died his estate records show that his

wife was entitled to one-fifth of the seven slaves he held. A neighbor wanted

one of them, Juggy Owens,

28, to be set free. Court records show Juggy was emancipated October 1, 1792.

She is the fifth-generation ancestor of Dana Elaine Owens (born March 18,

1970), known professionally as Queen Latifah, an American singer and actress.

The Keelings retained ownership of the Keeling House up through the Civil War

years until the house was sold to John Avery in 1881. At about that time it was

revealed that three slaves (Eliza

Willy/Wilroy, Wilson Willy/Wilroy and Samuel Willy/Wiroy) were listed in Solom Keeling's will as belonging to

him. He was one of the last Keeling House owners.

Frances Land House Built in 1805

The house standing today is possibly over two Older Houses, 1732 & 1640

Francis Land II (1604 - 1657) arrived in 1638. He brought

slaves to work his lucrative tobacco fields. By the mid-18th century his

plantation had around 20 slaves, typical for the tobacco plantations in the

area. The Lands were active in Lynnhaven Parish Church serving as Church

Wardens in 1647 and 1727.

A typical Grand

Manor House

like the Walke

Fairfield Manor House

Colonel Thomas Walke I (1642 – 1694) was an immigrant

from British-ruled Barbados. He made his fortune shipping goods to Barbados

from Hampton Roads and slaves back to Hampton Roads from Barbados. Built in

1720 by slaves, Walke's Fairfield estate contained several buildings and a grand manor

house. For 145 years the Walkes were dominant in the affairs of Lynnhaven

Parish Church and in local government, each generation leaving slaves to their

sons.

The Sauders'

Pembroke Manor House (1764 - present)

Acreage was given to Rev. Jonathan Saunders in 1694 by

the King of England. He provided

religious leadership for the growing Lynnhaven Parish Church from 1695 to 1700.

The Pembroke Manor House (still standing) was built in 1764 by his grandson

Captain Jonathan Saunders I (1726 – 1765) using slave labor.

Lynnhaven Parish / Old Donation Church

(1736 - present)

Parishes in Virginia frequently

either purchased or hired slaves for labor projects using bequeathed funds.

Another use of bequeathed funds was practiced by Lynnhaven Parish. The November

1762 will of Thomas Walke III instructed the Lynnhaven Parish vestry to

exchange property he left to the church for child bearing slaves. Apparently

having done so, in October 1767 a slave called Rachal was traded for another slave, apparently

one of better child-bearing age. Two years later on October 3rd, 1779,

the vestry records stated that slaves, named Harry, Lewis, Gefford, and Lydla, were “set apart for the said

Robert Dickson's Widow's Dower,” and after her death, these slaves were to

be used to benefit the education of poor male orphan children in Reverend Robert Dickson’s (1716-1777) free-school.

In general church-owned slaves were at a disadvantage

because no one individual had a concrete, personal financial interest in their

well-being. This created poor conditions for these slaves while significantly

strengthening the Anglican Church in Virginia during the eighteenth and

nineteenth centuries.

Rev. Anthony

Walke's Manor House (1782 – 1828) (a sketch)

Toward the end of the eighteenth-century leaders began to

talk about ending slavery. Most prominent was the Reverend Anthony Walke (1755

- 1814). He was the largest slaveholding minister in Tidewater Virginia. Reverend Walke and other social leaders of

the time, including Thomas Jefferson, were reluctant to confront this

deep-rooted socially accepted custom. The only acceptable solution in Walke’s

mind would be the prospect of freedom in years to come. He anticipated that his

son David would give them freedom, but when Anthony died, he had over

sixty-five slaves without a mention of their freedom in his will.

Charles McIntosh

(1812-1862)

The Thalia neighborhood was home to

George McIntosh (1768-1863), a wealthy Norfolk merchant, who lived at his Summerville Plantation Manor House

(no longer standing). The manor house required sixteen slaves to work the

plantation which initially took up most of the Thalia neighborhood. Just on the other side of the West Lynnhaven River from Summerville, Elizabeth Walke lived with her cousin Rev. Anthony Walke in the Walke

Manor House . George

often stood on his balcony looking out many evenings to see the beautiful Elizabeth standing out on her balcony.

No sooner had they been introduced than wedding plans were made. Their 1800 wedding was a grand affair in the small Lynnhaven Parish Church with days of celebration at their respective estates.

After the Walke Manor House burned down in 1828, George purchased the

land and had slaves build the Ferry Plantation House in 1830 (the house

standing today) for his son Charles Fleming McIntosh (1812-1862).

Henry Robert

Woodhouse (1811 - 1890)

@ Eastern Shore Chapel Cemetery.

@ Eastern Shore Chapel Cemetery.

Old Comfort (still standing) was built in 1832 for Henry

Robert Woodhouse (1811 - 1890) using slave labor. He was the 8th generation

ancestor of the first Woodhouse that settled in Lynnhaven Parish. When the war was over, and slaves freed, Henry's slaves all stole off in the middle of the night leaving behind tiny

black baby Jim who was

found the next morning in the kitchen and raised by the Woodhouse family.

"He agreed

to give me my manumission papers"

Toward the end of the eighteenth and into the early nineteenth century conditions began to

improve for some slaves as slave masters increasingly freed them through wills. In 1782, the Virginia General Assembly passed a manumission law (the act of an owner freeing his slave). Here are a few

examples: *Will of Thomas Woodhouse (Will Book II page 62) “Negro Max I give him his freedom and five hundred dollars.” April 8, 1812.

*Will of Emanuel Fentress (Will Bock II page 399) “I leave my four slaves to be free forever; man David, boy Daniel, woman Letty, girl Cloe for them and their heirs.”

*Ned Keeling (1770-1846) became a free man in 1815. Shortly after his master’s death, Catherine Collette, a white woman bought Ned in order to save him from slave traders. After five years Ned was able to buy his family their freedom through manumission, Ned’s wife Amy, and two children, Peggy and William. By 1830, Ned held property valued at $1,000.00 from his job as a drayman (delivering beer for a brewery).

19th Century

Slaves Working on Cotton Plantations

in the Deep South Under Harsh Conditions

in the Deep South Under Harsh Conditions

On into the nineteenth century slave conditions again

deteriorated. With the decline of tobacco and a shift to less profitable grains

requiring fewer slaves, their keep became a burden with a number of socially

extravagant Lynnhaven Parish plantation owners in debt to London Banks. Then

the “Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of 1807” turned plantation

owners’ fortunes around. No longer able to import slaves, plantation owners

sold their slaves to cotton plantations in the deep south where life in the

fields meant "working sunup to sundown six days a week and having food

sometimes not suitable for an animal to eat." Slave sales became a

highly successful business venture in the Virginia economy right up to the

Civil War. Between 1800 and 1861 as many as 500,000 African slaves were sold,

Richmond being the largest slave market, second only to New Orleans. For those

slaves left behind, most Virginia slaves owners had no thought of freeing them

since the system of human bondage continued to fuel their economic prosperity.

Harriet Tubman (1822 – 1913) born a slave, help hundreds of slaves reach freedom through a network of safe houses known as the Underground Railroad. She made 13 trips to the South, helping to free over 70 people. While she was sometimes featured in today’s classroom history books, they seldom mention other notable women of color, especially a famous Virginian, Isabella Gibbons (1836 – 1886). She lived and worked at the University of Virginia (UVA) as a slave. When the Emancipation Proclamation freed Isabella, she remained in Charlottesville and became a prominent member of the newly freed African American community as a schoolteacher. In 1914 UVA named a new residence hall after her and her husband in 2014, and her powerful words are engraved on the new (2020) Memorial to Enslaved Laborers (see the memorial below in this article). “Can we forget the crack of the whip, the cowhide, the whipping post, the auction block, the handcuffs, the spaniels, the iron collar, the negro-trader tearing the young child from its mother’s breast as a whelp from the lioness? Have we forgotten those horrible cruelties, hundreds of our race killed? No, we have not, nor ever will.”

Harriet Tubman Memorial Statue, Manhattan, New York - 2008. The statue, by sculptor Alison Saar, subtitled “Swing Low,” was dedicated on November 13, 2008. The back of the sculpture depicts stylized roots that are being pulled from the ground by Tubman’s resolute stride.

Four years before the start of the Civil War Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in Portsmouth, Virginia, built in 1857, quickly became known as a safe haven on the Underground Railroad. Slaves were hidden in a crawl space beneath the pipe organ. A network of friends and informants in the city helped those escapees find passage or stow away on ships heading north.

Harriet Tubman (1822 – 1913) born a slave, help hundreds of slaves reach freedom through a network of safe houses known as the Underground Railroad. She made 13 trips to the South, helping to free over 70 people. While she was sometimes featured in today’s classroom history books, they seldom mention other notable women of color, especially a famous Virginian, Isabella Gibbons (1836 – 1886). She lived and worked at the University of Virginia (UVA) as a slave. When the Emancipation Proclamation freed Isabella, she remained in Charlottesville and became a prominent member of the newly freed African American community as a schoolteacher. In 1914 UVA named a new residence hall after her and her husband in 2014, and her powerful words are engraved on the new (2020) Memorial to Enslaved Laborers (see the memorial below in this article). “Can we forget the crack of the whip, the cowhide, the whipping post, the auction block, the handcuffs, the spaniels, the iron collar, the negro-trader tearing the young child from its mother’s breast as a whelp from the lioness? Have we forgotten those horrible cruelties, hundreds of our race killed? No, we have not, nor ever will.”

Harriet Tubman Memorial Statue, Manhattan, New York - 2008. The statue, by sculptor Alison Saar, subtitled “Swing Low,” was dedicated on November 13, 2008. The back of the sculpture depicts stylized roots that are being pulled from the ground by Tubman’s resolute stride.

Harriet Tubman was not the first to use the Underground Railroad. Before her, Florida had an Underground Railroad network of safe houses and anti-slavery activists stretching into Florida where slaves found freedom at Fort Mose, but many going north were returned to their slave masters as the Fugitive Slave Law did not end until 1864.

Fort Mose was the first free black settlement in what is now the United States. There, enslaved under Spanish rule, blacks had more rights than the race-based slavery that flourished in the southern English colonies. By 1738 there were 100 blacks, mostly runaways from the Carolinas, living at Fort Mose. Many were skilled workers, blacksmiths, carpenters, cattlemen, boatmen, and farmers.

Located just north of St. Augustine, Fort Mose played an important role in the development of colonial North America when in 1845 Florida was admitted to the union as the 27th US state.

The University of Virginia (UVA)

UVA was founded by Thomas Jefferson in 1819 with students

committing unchecked abuse against their slaves by nearly beating them to death

for trivialities such as being slow to pick something up, and some of these

slaves were the ones who had built UVA. Charlottesville slaves would not see

relief until six decades later during the closing days of the Civil War. On

March 3, 1865 Union Army troops, under the command of Major General Philip

Sheridan, arrived in Charlottesville to free 14,000 slaves. They made up a

majority of Charlottesville’s residents including hundreds of slaves that were

owned by Thomas Jefferson in nearby Monticello.

As late as the twentieth century Charlottesville citizens

erected statutes of Confederate Robert E. Lee (1917) and Stonewall Jackson

(1921). As for slaves, about 1919 a

small marker was set into the sidewalk in Court Square Park. The plaque was not

to honor slaves, but only to note a historic place. As for a statue of Gen

Sheridan, his was installed in 1908, not in Charlottesville, but in Washington

D.C.’s Sheridan Circle.

Statue of Gen Sheridan, in Washington D.C.’s Sheridan

Circle.

Virginia’s Sin of Slavery is Only Half the Story Without Understanding Its Aftermath

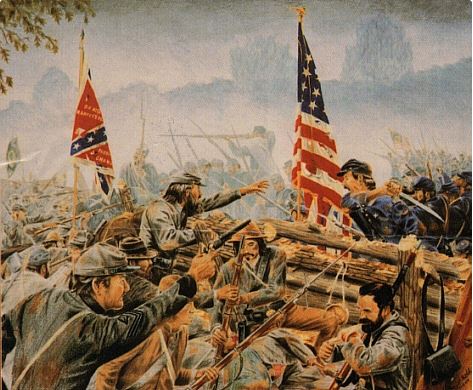

Battle of Fort

Sumter

April 12, 1861. The American Civil War began when the

Confederate Army fired on Fort Sumter.

Operations of the

Fugitive-Slave Law

In the beginning historians generally agree the war was

about freeing the slaves. However, President Abraham Lincoln was still

enforcing the Fugitive Slave Law, an indication he was not initially interested

in freeing the slaves but instead preserving the Union.

Right up to this day schools in

the eleven former Confederate States have been teaching the Civil War was

fought for states’ rights. But there is more to it that southern kids are never

taught. The Civil War was fought for states’ rights to enslave African

people. This is only one example of southern children being raised with little

information about slavery, and if at all, the true facts are whitewashed.

Ref. "Fort Monroe, the Key to the South," 2000, pg 37, by John V. Quarstein, on page 37, made this assertion.

August 6, 1861. This all became clear when Congress formally nullified the Fugitive Slave Law as provoked by Major General Benjamin Butler’s decision to make slaves “chattel property.” As commander of U.S. Union forces at Fort Monroe he reasoned that slaves were being used to support the Confederate economy and war effort, and that he could take possession of whatever property the Union needed to turn a Southern asset into a Union benefit. When runaway slaves heard they could be “contraband” of war, more than ten thousand found asylum at Fort Monroe. Using these slave assets, in one assignment, Butler sent Willis A. Hodges to Cape Henry to keep the lighthouse operational for Union ships and guard it from Confederate attack.

Ref. "Fort Monroe, the Key to the South," 2000, pg 37, by John V. Quarstein, on page 37, made this assertion.

August 6, 1861. This all became clear when Congress formally nullified the Fugitive Slave Law as provoked by Major General Benjamin Butler’s decision to make slaves “chattel property.” As commander of U.S. Union forces at Fort Monroe he reasoned that slaves were being used to support the Confederate economy and war effort, and that he could take possession of whatever property the Union needed to turn a Southern asset into a Union benefit. When runaway slaves heard they could be “contraband” of war, more than ten thousand found asylum at Fort Monroe. Using these slave assets, in one assignment, Butler sent Willis A. Hodges to Cape Henry to keep the lighthouse operational for Union ships and guard it from Confederate attack.

The first Cape

Henry Lighthouse was built in 1792. During the Civil War, to keep it

operational for Union ships, Major General Benjamin Butler sent black troops

from Fort Monroe to guard it from Confederate attack. Willis A. Hodges was the

first of these contraband freedmen lighthouse keepers. He carried drums of

whale oil up the slippery steps. Later during the reconstruction years

(1865-1877) Hodges became an influential leader in Princess Anne County, being

the county's first freeman elected representative.

Mary Smith Peake (1823 – 1862) & the Emancipation Oak

December 1863. During the time Major General

Butler maintained control of Fort Monroe, contraband freedmen sought out Mary Peake to teach

them and their children how to read and write. She held classes under a large

oak tree. Not long after her death, her students and their parents gathered

under the tree in December 1863 to hear the first Southern reading of the Emancipation

Proclamation issued on January 1, 1863 by President Abraham Lincoln giving 3.5 million slaves their

freedom. Ever since the tree has been known as the Emancipation Oak, located at

today’s Hampton University and designated as one of the ten Great Trees of the

World by the National Geographic Society.

Gen. Gordon Granger is shown on the above left, and on Galveston Island the marker describes the history surrounding the Emancipation Proclamation. Read the inscription @ https://www.galveston.com/whattodo/tours/self-guided-tours/historical-markers/juneteenth

(1861-1866) - After a four-year war costing the lives of as many as 850,000 (not counting slave causalities of which there were tens of thousands), on April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee fought the last battle surrendering his Confederate troops to Ulysses S. Grant, and 16 months later Confederate President Andrew Johnson declared a formal end to the conflict in August 1866.

1866 - Texas. For the few monuments erected in Confederate States for Union soldiers who fought during the Civil War, the German-American Treue der Union Monument is an exception. It commemorates 34 German-Texans killed for refusing to sign loyalty oaths to the Confederacy.

In Brunswick, Georgia a mural of Ahmaud Arbery is painted on a downtown building. The case has brought renewed criticism of a police department that, through one person’s efforts, the “I Run With Maud” movement has gone international. Jason Vaughn, a football coach and African American studies teacher at Brunswick High was a key figure in the push to investigate the death of his former football player Ahmaud, who was shot and killed after being chased by armed men while jogging in a local neighborhood in February 2019. After Ahmaud’s death, the investigation dragged on with no answers, and local leaders felt content to bury the episode. Emerging as a leading advocate for justice, Vaughn pushed for resolution challenging a town leadership that failed Arbery. Despite people telling Vaughn “to stop stirring trouble,” he nevertheless forged ahead garnering local support and media attention until the people involved in Arbery’s murder were arrested and charged.

June 19, 1865: In an effort to keep slaves suppressed,

the Emancipation Proclamation was not read at first in all Confederate States.

Not until two months after Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant,

effectively ending the war, did Texas get the news, almost two and a half years

after President Abraham Lincoln had issued the proclamation January 1, 1863. On

June 19, 1865 Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger landed on Galveston Island with more

than 2,000 Union troops and read “General Order No. 3” which was printed

in the Galveston’s newspaper the same day - “The people of Texas are

informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the

United States, all slaves are free.” Even though the proclamation expressly

exempted parts of the Confederacy that had already come under Northern control,

June 19, 1865 became celebrated as Juneteenth, freedom of slavery in

America. On June 3, 1979 the first state to make Juneteenth an official state

holiday was Texas’s black legislator, with Virginia becoming second on June 19,

2020 by executive order of Governor Ralph Northam. Gen. Gordon Granger is shown on the above left, and on Galveston Island the marker describes the history surrounding the Emancipation Proclamation. Read the inscription @ https://www.galveston.com/whattodo/tours/self-guided-tours/historical-markers/juneteenth

April 14, 1876:

The Freedmen’s Memorial in

Washington D.C. famously exhibits a standing Abraham Lincoln giving freedom to a

kneeling black man, whose chains are being broken. A huge parade involving

nearly every black organization in the city preceded the dedication of the

monument. The orator of the day, was Frederick Douglass. With blunt honesty, he

announced that Lincoln “was not . . . either our man or our model.” He

directly chastised Lincoln’s early advocacy to remove blacks from the country

as a solution after emancipation. Then the tone and purpose of his speech

shifted. Douglass brilliantly spoke to Lincoln’s actions as the birth of black

equality and rights. On June 26, 2020 as monuments of the past Confederate era were

being torn down, a few wanted the Freedmen’s Memorial also taken down, but others

felt it could be an honorable start for an epic process to replace a landscape

strewn with Confederate monuments, with monuments representing the story of

black freedom from one generation to the next. So much new learning could take place.

Ref: “Don’t

Tear Down the Freedmen’s Memorial,” June 26, 2016, the Washington Post, by

David W. Blight.(1861-1866) - After a four-year war costing the lives of as many as 850,000 (not counting slave causalities of which there were tens of thousands), on April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee fought the last battle surrendering his Confederate troops to Ulysses S. Grant, and 16 months later Confederate President Andrew Johnson declared a formal end to the conflict in August 1866.

1866 - Texas. For the few monuments erected in Confederate States for Union soldiers who fought during the Civil War, the German-American Treue der Union Monument is an exception. It commemorates 34 German-Texans killed for refusing to sign loyalty oaths to the Confederacy.

Ten months after the Civil

War ended, an enslaved woman who had been ripped away from her children started

looking for them. Elizabeth

Williams, who had been sold twice since she last saw her children,

placed a heart-wrenching ad in a newspaper: “INFORMATION WANTED by a mother

concerning her children,” Williams wrote March 17, 1866, in the Christian

Recorder newspaper in Philadelphia. Her ad was one of thousands taken out by

formerly enslaved people looking for lost relatives after the Civil War. Those

ads are now being digitized in a project called “Last Seen: Finding Family

After Slavery,” which is run by Villanova University’s graduate history

program in collaboration with Philadelphia’s Mother Bethel AME Church.

Reconstruction of the South - Promise Betrayed

After Lincoln was assassinated April 15, 1865, with reunification plans falling to his successors, Presidents Andrew Johnson (1865-1869) and Ulysses S. Grant (1869 - 1877), white supremacy gradually reasserted its hold on the South.

First to hit freedmen hard was land first given to them but then taken away. The most well-known was issued by Major General William Sherman January 16, 1865 promising thousands of freedmen 40-acres of land by "Special Field Order 15." In July 1866, all confiscated lands from whites were returned to their original owners by an act of Congress. Freemen could stay and work the land, but most left.

In 1883, the Supreme Court ruled that the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was unconstitutional and not authorized by the 13th or 14th Amendments of the Constitution, and in 1896, the Supreme Court further promulgated the “separate but equal doctrine” in Plessy v. Ferguson, thereby sanctioning a profusion of unabashedly discriminatory Jim Crow laws and effectively demolishing the foundations of the post-Civil War Reconstruction Era. However, freedmen were able to move freely, and six million fled the South while many stayed behind to experience mostly bad outcomes.

April 26, 2018 - The National Memorial for Peace and Justice. In the background columns hang down from the ceiling with the names of freemen hanged.

The outcome of those who stayed behind was finally documented in 2018 with the opening of a six-acre site in Montgomery, Alabama, dedicated to the lynching of more than 4,000 freedmen between 1877 and 1950, according to the Equal Justice Iniative's "Lynching in America" project, in a decades-long campaign of racial terror in the eleven deep southern states. The memorial site provides a sacred space for truth-telling and reflection about racial terrorism and its legacy. In the building a metal plate reads:

FOR THE HANGED AND BEATEN, SHOT, DROWNED, AND BURIED

FOR THE TORTURED, TORMENTED, AND TERRORIZED

FOR THOSE ABANDONED BY THE RULE OF LAW WE WILL REMEMBER

WITH HOPE BECAUSE HOPELESSNESS IS THE ENEMY OF JUSTICE

WITH COURAGE BECAUSE PEACE REQUIRES BRAVERY

WITH PERSISTENCE BECAUSE JUSTICE IS A CONSTANT STRUGGLE WITH FAITH

BECAUSE WE SHALL OVERCOME

During the Civil War

(1861-1865), on December 8, 1863, President Lincoln issued the Proclamation

of Amnesty and Reconstruction, a plan to reunify the country. This was followed by a

series of laws that opened up doors for freedmen; the 13th Amendment (1865)

abolishing slavery, the Reconstruction Act (1867) providing office holding

rights for freemen, the 14th Amendment (1868) granting equal civil rights, and

the Civil Rights Act (1875) granting equal rights in public spaces such as on buses and in restaurants. Now freemen

had a voice in government for the first time, winning election to southern

state legislatures and even to the U.S. Congress.

A New Day: Recently liberated slaves, who had belonged to Thomas F. Drayton, pose in 1862 on the Magnolia Plantation in South Carolina.

After Lincoln was assassinated April 15, 1865, with reunification plans falling to his successors, Presidents Andrew Johnson (1865-1869) and Ulysses S. Grant (1869 - 1877), white supremacy gradually reasserted its hold on the South.

First to hit freedmen hard was land first given to them but then taken away. The most well-known was issued by Major General William Sherman January 16, 1865 promising thousands of freedmen 40-acres of land by "Special Field Order 15." In July 1866, all confiscated lands from whites were returned to their original owners by an act of Congress. Freemen could stay and work the land, but most left.

Ref: “A Promise

Betrayed: Reconstruction Policies Prevented Freedmen from Realizing the

American Dream,” by Rick Beard, an

independent historian, author, and museum consultant, writes from Harrisburg, PA.

https://www.historynet.com/a-promise-betrayed.htm

In 1883, the Supreme Court ruled that the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was unconstitutional and not authorized by the 13th or 14th Amendments of the Constitution, and in 1896, the Supreme Court further promulgated the “separate but equal doctrine” in Plessy v. Ferguson, thereby sanctioning a profusion of unabashedly discriminatory Jim Crow laws and effectively demolishing the foundations of the post-Civil War Reconstruction Era. However, freedmen were able to move freely, and six million fled the South while many stayed behind to experience mostly bad outcomes.

April 26, 2018 - The National Memorial for Peace and Justice. In the background columns hang down from the ceiling with the names of freemen hanged.

The outcome of those who stayed behind was finally documented in 2018 with the opening of a six-acre site in Montgomery, Alabama, dedicated to the lynching of more than 4,000 freedmen between 1877 and 1950, according to the Equal Justice Iniative's "Lynching in America" project, in a decades-long campaign of racial terror in the eleven deep southern states. The memorial site provides a sacred space for truth-telling and reflection about racial terrorism and its legacy. In the building a metal plate reads:

FOR THE HANGED AND BEATEN, SHOT, DROWNED, AND BURIED

FOR THE TORTURED, TORMENTED, AND TERRORIZED

FOR THOSE ABANDONED BY THE RULE OF LAW WE WILL REMEMBER

WITH HOPE BECAUSE HOPELESSNESS IS THE ENEMY OF JUSTICE

WITH COURAGE BECAUSE PEACE REQUIRES BRAVERY

WITH PERSISTENCE BECAUSE JUSTICE IS A CONSTANT STRUGGLE WITH FAITH

BECAUSE WE SHALL OVERCOME

Virginia Beach's Seatack

A few of those who fled the south found their way to Virginia Beach’s Seatack. Seatack remained one exception to this time of racial terrorism in the south. Freedmen settled here because whites didn't see the future value of the swampy land. Freedmen not only moved in but also thrived in Seatack. They owned their own farms and built their own homes. They were craftsmen, builders, farmers, fishermen, and hunters. Whatever they needed, they built it with their own hands. Through hard work by Seatack citizens, life flourished. Despite being held back by white resistance, Seatack citizens continued to thrive. On October 15, 2011 the Seatack Civic League held their 200th Birthday Celebration, the first major African American community event ever held in Virginia Beach.

Setting the Example for a Better World

Bryan Stevenson started the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) and initiated the National Memorial for Peace and Justice (see above). By August 2016, EJI had saved 125 men from the death penalty, mostly blacks living in former Confederate States where they have embraced discriminatory “Black Codes” leading to the imprisonment of unprecedented numbers of black men, women, and children, who were returned to slavery-like conditions through forced labor. Mass incarceration today stands as a legacy of past abuses and continues to limit opportunities in most black communities. The United States has the world’s highest incarceration rate; 2.3 million with 70 percent being non-white. The average black man has more than a 1 in 3 chance of being imprisoned at some point in his life. (The movie "Just Mercy" portrays Bryan Stevenson's real-life story.)

Peace Monument, Atlanta Georgia. In 1910, the Old Guard of the Atlanta Gate City Guard, erected a monument in Piedmont Park to commemorate the efforts made over a thirty-year period to bring about unity between the North and the South. The Old Guard has rededicated the monument each year since. The Atlanta History Center has placed exhibition panels near the Peace Monument and contextualized markers near confederate monuments after Georgia state law prohibited monument removal.

In Brunswick, Georgia a mural of Ahmaud Arbery is painted on a downtown building. The case has brought renewed criticism of a police department that, through one person’s efforts, the “I Run With Maud” movement has gone international. Jason Vaughn, a football coach and African American studies teacher at Brunswick High was a key figure in the push to investigate the death of his former football player Ahmaud, who was shot and killed after being chased by armed men while jogging in a local neighborhood in February 2019. After Ahmaud’s death, the investigation dragged on with no answers, and local leaders felt content to bury the episode. Emerging as a leading advocate for justice, Vaughn pushed for resolution challenging a town leadership that failed Arbery. Despite people telling Vaughn “to stop stirring trouble,” he nevertheless forged ahead garnering local support and media attention until the people involved in Arbery’s murder were arrested and charged.

Bishop Barnett Karl Thoroughgood (1949 – 2012) is a shining example of an accomplished Seatack citizen and the many generations of freed Thoroughgood slaves. Reverend Barnett Thoroughgood, founder of the New Jerusalem Church of God in Seatack, was loved and respected. His February 10, 2012 funeral was attended by over 4,000.

Milton Thoroughgood Selden

Despite “massive resistance,” a few prospered. Born in Norfolk, Theodore Milton Thoroughgood Selden (1898 - 1922) was an exceptional young man at a time when freedmen students were practically unheard of in any law school, much less one of the country's oldest and most selective. He was one of eight children born to William Henry and Georgie Anna Thoroughgood Selden. Milton was not only intelligent, but a groundbreaker, one of the few freedmen of his era to receive education beyond high school. He enrolled at Lincoln University, a historically black college in Pennsylvania, graduating at the top of his class in 1919. He then transferred to Dartmouth, where he was elected into the prestigious Phi Beta Kappa Society. Graduating No. 2 in 1921, Milton entered Penn Law School but did not finish when he was killed in a train accident working as a porter to pay for his schooling. Milton's mother, George Anna Thoroughgood traces her genealogy back to two slaves, Mary and Frank, freed in 1853 by Mary Woodhouse and Frank Thoroughgood to become the first freed Thoroughgood’s. Mary and Frank were married in Princess Anne County by a Rev. John Buskin.

I Do Believe We Shall

Overcome - Some Day

1866: The Ku Klux Klan (KKK), an extremist hate group, during Reconstruction, was founded in the spring of 1866 in Pulaski, Tennessee with the aim of making the black man’s fate worse than when he was a slave. They led the South in a campaign of torture, lynchings, and church burnings.

August 1925: as many as fifty-thousand KKK staged a massive demonstration in Washington D.C.

November 25, 1915: the rebirth of the KKK was led by William J. Simmons, a circuit-riding minister, when he gathered a group in front of a burning cross. The new Klansmen hated blacks, Roman Catholics, and Jews alike, and for the next ten years they added to their list protection against inferior blood, more law enforcement, national patriotism, and power to the uneducated white worker. By 1925 the Klan membership had swelled to as many as six million. As the roaring twenties progressed, fewer people aligned with the Klan’s doctrine, but even after its original founding in 1866, the KKK is still an active, domestic terrorist organization (see article below - August 2017, Charlottesville, Virginia).

Mary Ann Shadd Cary was the

first African American woman to get a law degree in the United States. She

joined the growing women’s voting rights movement and with other women

attempted to vote in 1871, but was rejected by the Supreme Court based on the

inferior intelligence of women.

Sarah Parker Remond became

involved in women’s rights while studying in Britain. She is the only black

woman to sign the 1866 petition for women’s voting rights, along with some of

the period's foremost white female advocates for suffrage.

Mary Eliza Church Terrell was a

well-known African American activist who championed racial equality and women’s

suffrage in the late 19th and early 20th century. Her words, “Lifting as

we climb,” became the motto of the National Association of Colored Women

(NACW), the group she helped found in 1896, and she served as president from

1896 to 1901.

Ida Bell Wells-Barnett, born a

slave, was an early leader in the civil rights movement, and one of the founders

of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). She

helped organize the Chicago Alpha Suffrage Club in 1913 as a way to further

voting rights for all women.

1921 - Tulsa, Oklahoma was the site of one of the most vicious acts of

racial violence in U.S. history. An angry white mob attacked homes and

businesses in a thriving community known as “Black Wall Street,” killing

some 300 people and leaving thousands homeless. White resentment exploded into

two days of epic terror, wiping the most prosperous black communities off the

map, and for years afterwards there was a concerted effort to erase that history from news

archives and history books. Only recently Tulsa has tried to confront those

days of terror by examining its lingering impact by belatedly

addressing the racial bitterness toward black financial success that led white

people to burn a prosperous Oklahoma community to the ground. White violence

against black aspiration occurred elsewhere: Rosewood, Fla., in 1923;

Springfield, Ill., in 1908; and Elaine, Ark., in 1919. It happened after both

world wars to returning black servicemen, whose military rank and training

conflicted with America’s subordinate station for black men. Even today some

white people feel discomfort when black people are perceived to have

risen “above their station,” like a black President of the United States. Reference: “The

Diabolical Irony of Trump’s Decision to Speak in Tulsa,” the Washington

Post, June 14, 2020 by Michele L. Norris.

October 7,

1948: Strom Thurmond (1902 –

2003) a South Carolina U.S. Senator addressed a large crowd inside UVA’s Cabell

Hall. In a bitter rant against President Harry Truman’s civil rights program to

ban lynching and protection against racial discrimination, Thurmond thundered that

Truman’s legislation would “undermine the American way of life.” He warned

that he and his fellow Dixiecrats offered “the only genuine obstacle to the

rise of socialism or communism in America.” He was repeatedly interrupted

by applause and standing ovations. Thurmond’s extremist views began making their

way through southern cities connecting civil rights to a Red Communist plot

against America with blacks being used as pawns to advance this ideology.

Nearly seventy years later in 2017, only a few feet away from where Thurmond

had issued his hate-filled speech, hundreds of Klansmen and other far-right

extremists carried on with Thurmond's divisive rhetoric at the "Unite the Right" rally. This time there was

pushback from crowds that had had enough of speech designed to tear the nation apart

and degrade blacks (see article below - August 2017, Charlottesville, Virginia, Unite the Right rally).

1954 - Linda Brown sits beside her mother after the

landmark Supreme Court segregation ban.

In 1950 a black third-grader in Topeka, Kansas, named Linda Brown had to walk one mile through a railroad switchyard to get to her “black” elementary school, even though a “white” elementary school was only seven blocks away. Linda's father, Oliver Brown, tried to enroll her in the white elementary school, but the principal refused her entry. Oliver sued, and the case was eventually heard by the Supreme Court. In 1954 they ruled in Linda’s favor (1954 Brown v. Board of Education). Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site, Topeka, Kansas, commemorates the U.S. Supreme Court, Brown v. Board of Education decision to end racial segregation in public schools.

Protesting

Integration of Public Schools

Senator Harry F. Byrd declared that massive resistance would be the best course to take in dealing with school desegregation, and in less than two years,

Virginia mounted a campaign of “massive resistance” enacting laws designed to

block integration and defy the Supreme Court’s decision. Virginia Schools were told they would lose state funding if they integrated, which resulted in school closings in Warren County, Charlottesville, Norfolk, and Prince Edward County. On January 19, 1959 a district court declared school closings void. This set the stage for “white flight” out of Virginia cities that had large black populations. “Bussing” became the next step by the courts to end school racial imbalance, a system that brought black students into white schools. Virginia led the way to end busing when the Supreme Court in 1974 limited busing in Richmond, and in 1986 when Norfolk became the first city in the country to end busing.

The Virginia Civil Rights Memorial, Richmond State Capital Grounds, commemorates the fight to end massive resistance after the 1954 Supreme Court order banning school segregation.

June 11, 1963: At the University of Alabama Governor George

Wallace, in a symbolic attempt to keep his inaugural promise of "segregation

now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever" stood at the school

door to block the entry of two African American students. Federal officers

compelled Wallace to stand aside. On that evening President Kennedy spoke to the

nation. “Discrimination exists in every city, every State of the Union,

producing in many cities a rising tide of discontent that threatens the public

safety. We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the

Scriptures and is as clear of the American Constitution. If an American because

his skin is dark, ….cannot enjoy the full and free life which all of us want,

then who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed and

stand in his place?"

*Another sculpture shows a young marcher being grabbed by a police officer while his police dog aggressively lunges forward.

July 2, 1964, the Civil

Rights Act. Legislation had been

proposed by President John Kennedy in June 1963, before he was assassinated. President

Lyndon Johnson carried on pushing the legislation through Congress to become law on July 2, 1964.

It prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or

national origin, in public places, provided for the integration of schools

and other public facilities, and made employment discrimination illegal.

August 6, 1965 - President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act. Martin Luther King is seen here shaking hands with the President.

The Voting Rights Act was another milestone for black rights which finally gave all people of color the right to vote.

In his address before a Joint Session of Congress, Johnson said, "Our lives have been marked with debate about great issues, issues of war and peace, issues of prosperity and depression. But rarely in any time does an issue lay bare the secret heart of America itself. The issue of equal rights for American Negroes is such an issue. And should we defeat every enemy, and should we double our wealth and conquer the stars, and still be unequal to this issue, then we will have failed as a people and as a nation."

Nevertheless, a later Supreme Court decision weakened the enforcement of the voting rights act. Further,

black communities continued to face changes and reduction of voter locations,

denial of early voting, purges of voter rolls, stricter voter ID laws, and

worst of all, gerrymandering to maintain affluent community districts that

could afford to spend more, exacerbating inequities among schools.

1963 – 1968. These laws pushed through Congress by President Johnson were the most sweeping civil rights legislation since

Reconstruction. Southerners became frantic. They had lost the Civil War, and

now one of their own, Lyndon Johnson, carried on Kennedy’ civil rights proposed legislation.

He was asking them to suffer another defeat, the loss of a way of life in which

whites were supreme.

Racial hatred boiled over to the point that American leaders of the civil

rights movement were picked off, one at a time.

The Robert F. Kennedy Memorial in front of the New York State Supreme Court, Brooklyn Columbus Park was dedicated November 2, 1971. His quotes include this.. “Each time a man strikes out against injustice, or acts to improve the lots of others, he sends a tiny ripple of hope, and those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.”

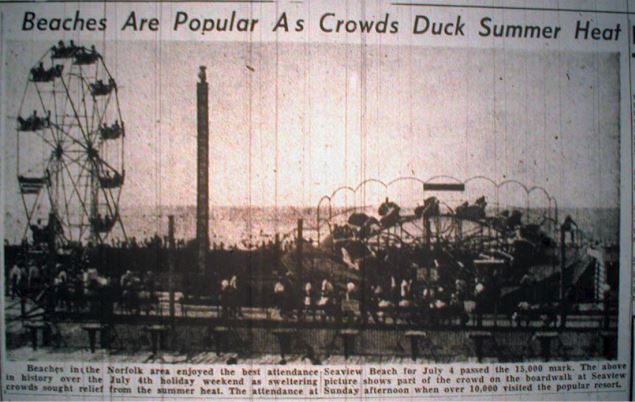

When Virginia Beach was founded in 1963 from Princess Anne County, segregation was still mainly in place and blacks were still denied the right to eat at lunch counters or spend nights at hotels on the oceanfront. Few black families wanted their children taunted for crossing "color lines." They saw their all black Sea View Beach and Amusement Park close (where Seagate Colony condominiums stands today on Cape Henry Beach), but they still could not attend ocean front beaches.

Virginians Begin to Learn About Their

"Unhealed History"

"Richmond's Unhealed History," by Benjamin Campbell, 2012. Campbell tells about Richmond's past "original sin," and a way forward to heal the nation's wounds.

Only recently have Virginians begun to confront long-ignored

truths about those enslaved and their struggles after their freedom right up to today. After the 2017 Charlottesville "Unite the Right" rally and the 2020 killing of George Floyd, people started showing up to demand institutional change in

the way communities and government purposely or unknowingly are giving black people an uneven hand.

Memorial to Enslaved Laborers at W&M

In 2007 students at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg began pushing for a memorial to acknowledgment its history of at least 180 enslaved African Americans who built the university. Expected to be completed in October 2021, the memorial is titled “Hearth” resembling a large brick fireplace with names of slaves to be etched on its wall. William Sendor, a 2011 school graduate, said he created his hearth design because it brought people together and because he was inspired “to figuratively illuminate the forgotten history and memory of these enslaved people who sacrificed and contributed immeasurably to William & Mary for over half of the College’s history, and then to physically illuminate a shared space for community gathering and reflection for generations to come.”

Memorial to Enslaved Laborers at UVA

Not only in Williamsburg, but at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, there has been a great awakening. The memorial is part of a larger, ongoing process at UVA spearheaded by the President's Commission on Slavery and the University that started in 2013. Completed in early 2020, the memorial responded to a deep need to address an untold and uncomfortable history of those African Americans who built the University. The memorial creates a space to gather, reflect, and acknowledge the names of 900 slaves engraved on the inside of the ring, with space for the remainder.

June 2013, Richmond, Virginia. Local citizens, on the twentieth anniversary of

“Unity Walk,” paraded through the heart of Richmond’s economic district on the historic slave

trail where more than 300,000 Africans slaves were held in Lumpkin’s Jail waiting to be traded. They

were tortured, torn apart from their families and sold like property. The final

stop of the walk concluded at the Reconciliation Statue. There walkers were

encouraged to think through inherited inequities of today’s black race and

practice ways to create personal and social transformation, racially just, and healthy

and inclusive communities.

A cascading fountain on the plaza

carries this inscription:

Liverpool, England; the Benin Region of West Africa; and Richmond, Virginia: During the 18th Century, these three places reflected on of the well-known triangles in the trade of enslaved Africans. Men, women and children were captured in West and Central Africa and transported from Benin and other countries. They were chained, herded, loaded on ships built in England and transported through the unspeakable horrors of the Middle Passage. They were imported and exported in Richmond, Virginia and sold in other American cities. Their forced labor laid the economic foundation of this nation.

Liverpool, England; the Benin Region of West Africa; and Richmond, Virginia: During the 18th Century, these three places reflected on of the well-known triangles in the trade of enslaved Africans. Men, women and children were captured in West and Central Africa and transported from Benin and other countries. They were chained, herded, loaded on ships built in England and transported through the unspeakable horrors of the Middle Passage. They were imported and exported in Richmond, Virginia and sold in other American cities. Their forced labor laid the economic foundation of this nation.

August 2017, Charlottesville, Virginia. The violent “Unite the Right” rally was a clarion call for people to stand up to these white supremacists who were openly exhibiting hatred against blacks.

Hundreds of far-right extremists descended on the city ostensibly to protest the removal of a Confederate

statue from a local park. Dubbed “Unite the Right,” the gathering was

the largest and most violent public assembly in decades of white supremacists, KKK, skin heads and other radical groups. James

Alex Fields, Jr. of Ohio received two life sentences plus 419 years for

deliberately driving his car into a crowd of protesters, killing Heather Heyer and injuring dozens more. Unite the Right advocates have since demonstrated a resurgent of

their cause despite the fact that many who participated at Charlottesville

have lost their jobs and been rejected by friends and family, imprisoned, and hit with travel bans.

July 2019 - Dr. Marcus Martin, UVA’s Vice President for Diversity and Equity, addresses the audience during the inaugural observance of Liberation and Freedom Day.

By a unanimous vote on July 1, 2019, the Charlottesville City Council established a new city holiday, Liberation and Freedom Day, to be celebrated on March 3 each year, the day General Sheridan liberated 14,000 slaves.

Virginia was America’s wealthiest and most populous state until the Civil War, and after the war Virginia lost its influence largely because it took on a role of leadership by encouraging the former Confederate States to make black lives worse than slavery by initiated a campaign of racial terror - torture, lynching, incarceration, and church burning.

*Between 1785-1985 Black Codes were used to keep blacks incarcerated for even trivial charges. As many as 200,000 blacks were forced into back-breaking labor in coal mines and lumber camps. They lived in squalid conditions, chained, starved, beaten, flogged and sexually violated. They died by the thousands from injury, disease and torture.

*Between 1877 and 1950, more than 4,400 blacks were tortured and then hanged, including 71 blacks in Virginia, but that Virginia proportionately small number belies the fact that, except for Texas, Virginia had executed more people than any state with the huge preponderance being black.

*Between 1921 and 1996 there have been forth-five attacks, three in Virginia, against black churches in the form of arson, bombings, mass murder, hate crimes, and white supremacist-propelled domestic terrorism.

*Still, America is not out of the woods because of various restrictions on blacks. The most devastating of all is the criminal justice system. As late as 2010, the rate of incarcerations in Virginia was 6 blacks for each white, leaving a legacy of black felons existing under the weight of various forms of discrimination in housing and voting.

But, especially in Virginia, things are changing under the leadership of Governor Ralph Northam (Jan 2018 to Jan 2022 - the Virginia term limit). He has become a champion, leading Virginia to an awakening of its "original sin" by repudiating racism. His example is helping to bring the Virginia economy and citizen pride back from its 160-year-long nightmare of racial wrong, which is also setting the example for the other former Confederate states.

*On June 4, 2019, Governor Northam issued an executive order setting up a commission to examine Jim Crow area legislation still remaining on the books.

*In 2020 Governor Northam championed the abolishment of the death penalty which is now a law.

*On August 24, 2020 Governor Northam signed an executive order establishing the Commission on African American History Education. In their final report he said, “The Commission’s recommendations will ensure that Virginia’s history standards reflect the complexity of our past, help students understand how present-day challenges are connected to this history, and provide teachers with more resources to engage in anti-racist work. This is important because the more our students know, the more our students can do to help build a better future for our Commonwealth and our country.”

*Between 1785-1985 Black Codes were used to keep blacks incarcerated for even trivial charges. As many as 200,000 blacks were forced into back-breaking labor in coal mines and lumber camps. They lived in squalid conditions, chained, starved, beaten, flogged and sexually violated. They died by the thousands from injury, disease and torture.

*Between 1877 and 1950, more than 4,400 blacks were tortured and then hanged, including 71 blacks in Virginia, but that Virginia proportionately small number belies the fact that, except for Texas, Virginia had executed more people than any state with the huge preponderance being black.

*Between 1921 and 1996 there have been forth-five attacks, three in Virginia, against black churches in the form of arson, bombings, mass murder, hate crimes, and white supremacist-propelled domestic terrorism.

*Still, America is not out of the woods because of various restrictions on blacks. The most devastating of all is the criminal justice system. As late as 2010, the rate of incarcerations in Virginia was 6 blacks for each white, leaving a legacy of black felons existing under the weight of various forms of discrimination in housing and voting.

But, especially in Virginia, things are changing under the leadership of Governor Ralph Northam (Jan 2018 to Jan 2022 - the Virginia term limit). He has become a champion, leading Virginia to an awakening of its "original sin" by repudiating racism. His example is helping to bring the Virginia economy and citizen pride back from its 160-year-long nightmare of racial wrong, which is also setting the example for the other former Confederate states.

*On June 4, 2019, Governor Northam issued an executive order setting up a commission to examine Jim Crow area legislation still remaining on the books.

*In 2020 Governor Northam championed the abolishment of the death penalty which is now a law.

*On August 24, 2020 Governor Northam signed an executive order establishing the Commission on African American History Education. In their final report he said, “The Commission’s recommendations will ensure that Virginia’s history standards reflect the complexity of our past, help students understand how present-day challenges are connected to this history, and provide teachers with more resources to engage in anti-racist work. This is important because the more our students know, the more our students can do to help build a better future for our Commonwealth and our country.”

January 2, 2019 -Representatives John Conyers and Shelia Jackson Lee introduce

H.R.40 to establish a commission to study and develop reparation

proposals for African-Americans (blacks). The commission is charged with examining slavery and

discrimination in the colonies and the United States from 1619 to the present

and recommending appropriate remedies.

March 6, 2020 - Newport News. the Episcopal Diocese of Southern Virginia and the Episcopal Church Center sponsored a two day “Walking Toward Truth Pilgrimage,” commemorating the 1619 arrival of the first enslaved Africans. The pilgrimage was an important step in the church’s ongoing journey toward racial healing, reconciliation, and justice. People were asked to learn about past wrongs of the church’s role in slavery and later segregation, a history the church allowed to be all but forgotten until recently. No Episcopal parish has been a witness to a longer span of American history than St. John’s Episcopal Church in downtown Hampton. Most black Episcopalians worshiped at St. Cyprian’s Episcopal Church founded in 1905 because St. John’s didn’t welcome blacks. More than a century later, St. John’s opened its doors to worshippers of all races and backgrounds. Telling about the church’s past is a critical component of the “Truth” initiative.

May 25, 2020, Minneapolis - By a policeman kneeing on George Floyd's neck for almost nine minutes while unarmed and crying for his mother and saying he could not breathe, he became unresponsive in the last two minutes. The killing sparked continuous days of protests, but unlike past protests this one resulted in a

"perfect storm," a particularly slow and gruesome murder of a

black man completely unarmed and incapacitated as he pleaded for help with no

split-second decision from a policeman fearing for his life, all recorded on cameras

by onlookers.

Governor of Texas Greg

Abbott said after reviewing the picture of George Floyd being killed, "This

is the most horrific tragedy I've ever personally observed, but George Floyd is

going to change the arc of the future of the United States" He went on

to promise to pursue policing reforms in Texas. He was not alone as all over

the country, legislatures rushed to reinvent their police force.

Then – March 7, 1965. Led

by John Lewis six hundred nonviolent protesters marched toward Selma, Alabama.

They were stopped by Alabama State troopers and local police who shot tear gas

and proceeded wading into the crowd beating them, ultimately hospitalizing over

fifty people.

Designed

by artist Sean Schwab, the sixty-five-foot high John Lewis mural towers over the

corner of Auburn Avenue and Jesse Hill Jr. Drive in Atlanta’s Sweet Auburn

district. On August 24, 2012, John Lewis spoke at the mural dedication, and on

Saturday, July 18, 2020, the day after Lewis died, mourners flocked to the mural

to honor a “true hero” paying their respects to the man and his legacy who

sought to convert racial discrimination into black-white amity, the oneness of

humankind.

Then - August 28, 1963 - Washington D.C. The “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom,” was capped off by Martin Luther King Jr. Standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial, King delivered his historic "I Have a Dream" speech to 250,000 people, one of the largest political rallies for human rights in United States history. The march was credited with helping to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Now - June 4, 2020 - Washington D.C. Fifty-seven years later as rallies for human rights continued in hundreds of cities worldwide over the killing of George Floyd, some in Washington D.C. paid a visit to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial. Organized by teenagers who founded the group "Faces of the Future," they listened to King’s historic “I Have a Dream” speech and wept that his dream was not yet fulfilled. King's speech ended with ….“When we allow freedom to ring from every city and every hamlet, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, ‘Free at last, Free at last, Great God a-mighty, we are free at last.’”

Protests continued as hundreds of thousands of demonstrators marched in 140 cities across the country and in dozens of cities in other

countries, all marching to show solidarity over the killing of George Floyd and

racial injustice.

June 5, 2020 - D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser had city workers block off a two-block section of 16th Street NW, located just outside of the White House, for the painting of a mural featuring the words “Black Lives Matter” (BLM) in 35-foot-tall yellow letters, all in Caps. This portion of 16th Street was officially renamed by the mayor, “Black Lives Matter Plaza NW.”

Black Lives Matter Plaza NW

June 11, 2020 - Richmond. Protesters pulled down the 1907 statue of Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States, positioned in front of the "Monument to the Confederate States of America, 1861-1865," one of a number of monuments removed or damaged in the wake of George Floyd protests.

Rita Davis,

legal counsel to Virginia Gov. Northam, speaks during a news briefing.

June 9, 2020: Governor Northam told the world that

the statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee in Richmond would come down.

But then lawsuits hit which the governor pledged to fight. He asked Davis, the

great-great-granddaughter of enslaved people, to explain his position at a news

briefing. Her voice broke with emotion as she said that the statue was designed

to “minimize a devastating evil” and that removing it “takes us a

step closer to reclaiming the truth of Virginia’s history . . . for all Virginians. I

want this statue to come down, but I want it to come down because there is a

consensus in Virginia saying that that’s not who we are anymore.”

Ref: “Behind Northam’s Statue Push: A Descendant of Slaves,” the Washington Post June 26, 2020, by Gregory S. Schneider

Ref: “Behind Northam’s Statue Push: A Descendant of Slaves,” the Washington Post June 26, 2020, by Gregory S. Schneider

August 2, 2020 - In the article on the Virginian Pilot front page (Discussions

about Racism) Rev. Bob Randall, Rector of Old Donation

Episcopal Church, said, “Knowing the truth, the good, the bad and the ugly,

helps us start to repair the breach in our world and chart a Godly path of

action for our parish.”

April 19, 2021, the Greensboro, N.C. Civil Rights Museum. As the first woman of color to hold a nationally elected office, Vice President Kamala Harris sat in the same spot at a lunch counter where Rosa Parks sat on December 1, 1955. Rosa Parks refused to move, setting off a one-year bus boycott and “sit-in” crusade.

After her visit, Harris told the nation, “America has a long history of systemic racism. Black Americans, and Black men in particular, have been treated through the course of our history as less than human. Black men are fathers and brothers and sons and uncles and grandfathers and friends and neighbors.”

America takes two steps forward and then one step back. George Floyd’s death inspired a wave of soul-searching about the roles that race and racism still play in American life, but in less than a year after Floyd's death, critical race theory (CRT) emerged among conservatives as a pushback against “Black Lives Matter.” CRT, a psychological defense for the ones in power, cited as Un-American, opening up the history of enslaved people from the 1619 Project to K-12 curriculums. BLM people have tried to push back, but CRT is an emotional defense against change, and not one based on fact.

Ref: “Why Conservatives Really Fear Critical Race Theory,” by Christine Emba, the Washington Post, May 27, 2021

If we ignore past history, as some suggest, we harm our country as a free and open society.

The following example, more than any other argument, shows why our rich history cannot be hidden. In 2020 Ed Allison, a teacher at Granby High School in Norfolk, received approval from Virginia to make changes to the social studies curriculum by allowing his students to make a field trip to Fort Monroe to find out about the “1619 Project,” which allowed his students to share what they had learned at the UN’s 12th Annual Global Student Conference. Their project, “Ending Slavery’s Legacy of Racism: A Global Imperative for Justice,” was developed by his students working with Fort Monroe archivists centered around 1619 when the first African slaves were brought to the American colonies arriving at Fort Monroe.

The UN program had about 500 students from 30 different countries in attendance. This was the first time Allison’s students had interacted with students from other countries who presented their local histories. It gave Allison’s students a chance to present a rich factual history they had worked hard to research.

One of Allison’s students, junior Aren De La Ross, made a video focused on the arrival of the first Africans at Fort Monroe. The video was featured on the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) website. La Ross said, “I feel like one of the biggest things I learned from the project is that there can be a lot of history that’s hidden. I know a lot of people who have been to Fort Monroe, including myself, who just had no idea about the rich history hidden in the port.” Allison’s project couldn’t have provided a stronger justification for his students to learn historical facts, examine various perspectives and draw their own conclusions. Allison added, “I think it’s where education needs to go. We’re working with the community, we’re working with Museums, we’re working with the national parks, we’re working with UNESCO. To me it’s really refreshing, as an educator for 20 plus years, to be able to be part of this and create this in my course curriculum.”