The eighteenth century was referred

to as the “Golden Age” and marked a

pronounced advancement for Lynnhaven English settlers who had labored

hard during the seventeenth century to transform a wilderness land occupied by

unfriendly Indians into a rich and prosperous one with large estates. The English colonists of Lynnhaven Parish enjoyed prosperity during the so called “Golden Age”, but that prosperity was based on the brutal reality of slavery. This transformation can be marked in the difference between several existing sixteenth and

seventeenth century homes. With little time and money to build, seventeenth homes

were simple two-room cottages. Large chimneys were built for cooking inside and

not moved to freestanding kitchen buildings until the eighteenth century. The seventeenth century homes called “hall-and-parlor cottages” still in

existence include the 1634 John B. Dey House, the 1636 Adam Keeling House (not the house standing today), the 1637

John Lovett House, the 1649 Weblin House, and the 1690 Lynnhaven House.

The 1690 Lynnhaven House is the last of these seventeenth century two room houses before much larger Georgian/Federal style homes were constructed in the prosperous eighteenth century of the Golden Age.

When Virginia Beach purchased the Adam Thoroughgood House from Norfolk (now called simply the Thoroughgood House), the city contracted a firm to take wood samples of the house. Using these results, they re-dating the house from 1641 to 1719. However, this new date has been called into question. Should the real date of construction be 1641, 1680 or 1719? For this discussion please visit "Old Homes," and select house number 6 at http://1bob9.blogspot.com/2009/06/old-homes.html

The 1690 Lynnhaven House is the last of these seventeenth century two room houses before much larger Georgian/Federal style homes were constructed in the prosperous eighteenth century of the Golden Age.

Compare the last of the 17th century hall-and parlor cottages

with the much larger first of the 18th century houses.

Those eighteenth century homes

still standing include the 1730 Green Hill Plantation House, the 1732 Francis

Land House (not the house standing today), the 1752 John Biddle House,

the 1759 Upper Wolfsnare House, the 1764 Pembroke Manor House, and the 1764

Poplar Hall House. The Francis Land House standing today does not fit into the early Georgian style as the first house burned down and the one standing today was built in 1805 over the burned out ruins of the first house, a practiced because the land had already been cleared of the large tree forest in early Lynnhaven. When Virginia Beach purchased the Adam Thoroughgood House from Norfolk (now called simply the Thoroughgood House), the city contracted a firm to take wood samples of the house. Using these results, they re-dating the house from 1641 to 1719. However, this new date has been called into question. Should the real date of construction be 1641, 1680 or 1719? For this discussion please visit "Old Homes," and select house number 6 at http://1bob9.blogspot.com/2009/06/old-homes.html

Grace Sherwood - the Witch of Pungo

(1660 – 1740)

In 1916, 215 years later, Old

Donation’s Senior Warden, Judge White revisited this cold case with Charles

Sherwood, the man who rebuilt the church from its ruins. During the time he spent with Charles, Judge

White made an exhaustive study of James and Grace Sherwood which he

published in 1924 under the title “Gleanings

in the History of Princess Anne County.” Did Judge White sow in Charles’

mind a way to get payback for the church’s transgressions against his two descendants,

James and Grace? As a builder he should have known the roof of Old Donation Church needed bracing to

keep it from pushing outwardly against the walls. The insertion of five metal

rods satisfied all concerned until April 17th, 1960 during an Easter service

when the walls began to separate. Inspection found Charles Sherwood had tied

the five rods into nothing, a time bomb just waiting for the roof to cave in. Luckily

it didn’t.

This 1920 photo shows the metal rods

installed but later found to be just stuck in the wall and not tied to the wall

Until 1731 slave owners were

allowed to bring their slaves to Lynnhaven Parish Church where they sat in the

balcony and took communion outside. For whatever reason the vestry made the

unwise decision to no longer allow slaves in the church at all. Not content to

stand outside during the long services, the slaves began to talk of insurrection.

When this was discovered, the instigators were severely punished. Nervous church members began carrying their rifles to

church on Sunday less they be stolen by slaves.

Soon the second Lynnhaven

Parish Church, known as the Brick Church or Mother Church, built in 1692,

became unsuited for a congregation that had progressed in wealth and social

status. In the place of the court house and jail where Grace Sherwood was

incarcerated for over seven years, a new and larger church was completed in 1736.

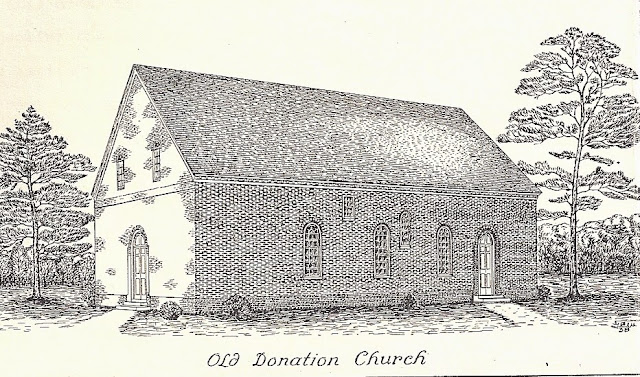

Church 3 (current church) is depicted

here after 1767 when the side door was moved about eight feet from the end of

the long south wall to its present location. The entrance narthex and side

sacristy were added during reconstruction in 1916.

The church continued to prosper

under the Reverend Henry Barlow (serving for 18 years) and then Reverend Robert

Dickson (serving more than for 27 years). When Reverend Robert Dickson became

Rector in 1748 he took over running a public school for orphaned children, and

in order to continue the school Anthony Walke proposed the old Brick church be

used for the school rather than be torn down. For 28 years Reverend Dickson invested

his energies in seeing that the orphan children became prosperous respected

citizens. This was not the case for Bruton Parish, less than fifty miles to the

north. There the church ran a workhouse, a complex of buildings near Capitol

Landing on a hilltop overlooking Queens Creek. Under Reverend Thomas Dawson the

1755 vestry record states that the workhouse was a place “where the poor might be more cheaply maintained and usefully employed,"

because "providing for the poor of

the said Parish hath always been burdensome” and the church should "compel the Poor of their Parish to dwell and

work in the said House under whatever restrictions the House might impose.”

The plight of children who lived in workhouses in Virginia was far from happy,

and mortality rates were high.

On Nov 21, 2012 a plaque recording Rev. Robert Dickson’s

service to the church, orphan boys’ school, and his donation (for which the

church is now named) was installed on the back wall of the church opposite the

Adam Thorowgood plaque.

During the heyday of the Golden

Gage Lynnhaven Parish Church became more of a social institution than a

religious one, and Sundays provided the occasion to socialize and transact

business. Services were long and held only every other week as some had quite a

distance to travel, the fastest way being by water. Being part of the Church of

England, Lynnhaven Parish Church was supported by taxation, and the church

vestry set tax rates and collected the money, usually in the form of tobacco.

Beginning in the 1730’s Presbyterians and Baptists began to protest the tax and

steal away poorer church members into their primitive churches while railing

against the easy life of the Lynnhaven Parish Church gentry. By the 1760’s a

number of Lynnhaven Parish Church members found themselves in debt due to their

luxurious and extravagant way of living. Exemplifying this downward spiral was David

M. Walke (1800-1854), son of the famous Lynnhaven Parish Church Reverend

Anthony Walke (1755-1814). After his father died David used the Walke Manor House,

site of today’s Ferry Plantation House, for gambling parties. At one of them,

in 1828, a drunken guest tipped over an oil lamp and burned the plantation to

the ground. Sometime in the early 1850’s

Author Bishop William Meade (1789-1862) wrote about a conversation he had long ago

with David Walke. “Formerly this was one

of the most flourishing parishes in Virginia. The social class, the rich feast,

the card-table, the dance, and the horse-race, were all freely indulged in

through the county. And what has been the result? The causes of bankruptcy and

ruin [were] cards, the bottle, the

horse-race, the continual feasts, - these were the destroyers.” On the side

of the most formidable and tallest tombstone in the church graveyard is David’s

inscription that, “acknowledges with

shame, having fallen far short of living in strict obedience to its holy precepts

and commandments.”

The tallest gravestone in Old Donation cemetery is David Walke (1800 - 1854), 6th child of Rev. Anthony Walke, III (1755 – 1814). The gravestone, along with other Walke stones, were moved from the Kempsville Fairfields Walke Cemetery in the 1930’s after being found enclosure in a hog pen.

The tallest gravestone in Old Donation cemetery is David Walke (1800 - 1854), 6th child of Rev. Anthony Walke, III (1755 – 1814). The gravestone, along with other Walke stones, were moved from the Kempsville Fairfields Walke Cemetery in the 1930’s after being found enclosure in a hog pen.

Leading up to the Revolutionary War (1775–1783), family

feuds started. Primarily the old, the English Loyalists, wanted to keep the

status quo. They worried about what would replace a British government

dictating Anglican authority. The young, American Patriots, wanted independence

and freedom from the King. Here is the story of two families who split their

allegiance.

Edward Hack Moseley, Sr. (1717-1783) was loyal to King George III, and enjoyed the social life of Virginia Governor Lord Dunmore right up until 1775 when the unpopular Lord Dunmore was forced out of Virginia in skirmishes leading up to the Revolutionary War. His son, Col. Edward Hack, Jr. Moseley (1743 - 1814) was a loyal patriot during the war, father and son standing on opposite sides, but this evidently did not affect their relationship.

Edward Hack Moseley, Sr. (1717-1783) was loyal to King George III, and enjoyed the social life of Virginia Governor Lord Dunmore right up until 1775 when the unpopular Lord Dunmore was forced out of Virginia in skirmishes leading up to the Revolutionary War. His son, Col. Edward Hack, Jr. Moseley (1743 - 1814) was a loyal patriot during the war, father and son standing on opposite sides, but this evidently did not affect their relationship.

May 17th, 2014, a wreath-laying

ceremony to mark

a new gravestone for Patriot Col Edward Hack Moseley, Jr.

The stub of his original gravestone can be seen just above the rose,

the oldest grave in the cemetery with remains.

a new gravestone for Patriot Col Edward Hack Moseley, Jr.

The stub of his original gravestone can be seen just above the rose,

the oldest grave in the cemetery with remains.

Another family that stood on

opposite sides was Captain Jonathan Saunders I (1726 – 1765) and his son Captain

John Saunders II (1754 - 1834). Saunders II chose to side with the British and his home, Pembroke

Manor, fell into the ownership of Princess Anne County in 1779.

Pembroke Manor House on Constitution Drive, just off Independence Blvd (as pictured above) was built by slave labor in 1764 by Captain Jonathan Saunders I.

The grave of Captain John Saunders I (1726-1765) was moved from Pembroke Manor without remains to the Old Donation Cemetery, the oldest marker in the cemetery.

Pembroke Manor House on Constitution Drive, just off Independence Blvd (as pictured above) was built by slave labor in 1764 by Captain Jonathan Saunders I.

The grave of Captain John Saunders I (1726-1765) was moved from Pembroke Manor without remains to the Old Donation Cemetery, the oldest marker in the cemetery.

Capt. Jonathan Saunders (1726 –

1765), “a person of great piety and a

most humane Disposition”

The Revolutionary War was all around Princess Anne County. The burning of Norfolk in January 1776 followed the November 1775 battle of

Kemp's Landing. In March 1781 the Battle of Cape Henry came even closer to Princess Anne County. In

early September 1781 word began circulating that Admiral deGrasse’s French

fleet was lying in wait at the mouth of the Lynnhaven Inlet to intercept a British fleet sailing

to Yorktown. For five days Lynnhaven Church members helped deGrasse load supplies onto his ships. On Wednesday morning the 5th of September, the British fleet

was spotted at the mouth of the Chesapeake. Taking most of the day to navigate the then small channel of the Chesapeake Bay, the battle did not start until late in the afternoon. French and British naval forces

exchanged cannon fire for about 2-1/2 hours on the fist day of this epic sea battle which continued for several more days. It resulted in preventing the British fleet from resupplying General Cornwallis at Yorktown, crucial in General Washington’s defeat of Lord

Cornwallis at Yorktown.

Standing on the shoreline that

September 1781 day were the Lynnhaven Parish Church families of one year old John

Brownley, three year old Anthony Walke, and twelve year old John Henderson. Thirty-two years later those three patriots would serve

as members of the Princess Ann County Militia in capturing the first English

ship off Cape Henry less than a month after the War of 1812 began. They are

buried in the Old Donation Church cemetery.

September 5, 1781 Battle of the Capes

- French (left) and British (right) ships

After the Revolutionary War, in addition to

James Madison, the Father of our Constitution, our church had an important hand

in voting for a central government. The

Articles of Confederation (1781) helped keep some local control over a church

weakened by the political power, wealth, and social prestige lost by English

rule. Five years later the stage was set

in Lynnhaven for replacement of the Article of Confederation by the present

U.S. Constitution. Anthony Walke and his distant cousin Thomas Walke IV (1760 –

1797) were chosen to represent Princess Anne County at the 1788 Virginia

Constitutional Convention because of their family status. Coming into the convention they represented

the Federalists from Tidewater, landowners whose financial policies aligned

with a strong central bank which would solidify the thirteen colonies

financially into one by removing any trade barriers. In order for the Constitution to become law,

two-thirds of the thirteen states had to ratify it. After New Hampshire became

the ninth state, even though Virginia had yet to vote, they along with New York

were locked in bitter debates. Their failure to ratify would reduce the new

union by two highly populated wealthy states, geographically splintering the

new nation. Voting in favor of the Constitution delegates from the Northern

Neck, the Shenandoah Valley and western counties, along with both Walkes, on

June 25, 1788, by a narrow margin, made Virginia the tenth state to approve the

new Constitution. With Virginia voting

yes, New York caved and also by a narrow majority approved the Constitution.

Rev. Anthony Walke's (1755-1814) stone was moved from the

Fairfields cemetery in Kempsville to the Old Donation Cemetery in the 1930's.

Up until 2015, the stone was not understood to be that of the famous Rev. Walke.

Along with the new government and freedom from Britain, the fears of the older gentry became true. With the British government no longer welding its Anglican authority over Americans, the church lost its tithing tax and the practice of younger sons entering the ministry or purchasing a commission in the army or navy. Without the protection of English church laws, new denominations drew people away from the Episcopal Church, and since there were no longer any bishops in the colonies to fight for the church, Princess Anne County began confiscating some of the county's oldest historical Episcopal Church properties after the church membership had faded away. Of the 107 Virginia parishes before the Revolutionary War, only 42 survived. Lynnhaven Parish was one of those 42.

At the turn of the century Rev.

Walke held our church together by conducting captivating sermons. He was famous for rushing off in the middle of

sermons to join the hunt on his horse Silverheels tethered near the door. When he returned late in the day he’d finish

preaching to church members who spent all day socializing and picnicking.

Rushing off in the middle of a sermon,

Reverend Walke joins the Fox Hunt

Marking the close of the eighteenth

century, Lynnhaven Parish hosted the wedding of the century. Rev.Walke’s

niece, Elizabeth Walke (1784-1855) lived with him in the Walke Manor House, the largest and grandest home in Lynnhaven Parish (location of today's Ferry Plantation House). Just across the West Lynnhaven

River was the estate of George F. McIntosh's (1768-1863) Thalia Summerville (location of today's Steinhilber's Restaurant).

Walke Manor House (1st Ferry Plantation House) built in 1782, destroyed by fire in 1828.

George McIntosh's Summerville, built in 1751 (site of today's Steinhilber Restaurant)

George first caught sight of Elizabeth standing on her porch

gazing across the moonlit river. Even though George, a wealthy Scottish

merchant, was twice her age, the couple were soon mingling at eloquent soirees

and taking week-long excursions to the Cape Henry bay-shore; having sent

servants ahead with tents, furniture and refreshments; all hosted by their

respective plantations. Their wedding in 1800 at Lynnhaven Parish Church was a

most grand affair and a way for the people of Lynnhaven Parish Church to take

their minds off congregants abandoning Lynnhaven in favor of a more prosperous

Kempsville.

Even though there were dark clouds on the horizon for Old

Donation and its surrounding Princess Anne County, America was growing by

freely granting citizenship to immigrants with the U.S. population almost

doubling between 1790 and 1810 to more than seven million. American merchants

were growing rich from the European wars. While the French and English sank

each other’s ships, neutral Americans traded with both sides. Thurmer Hoggard

III’s (1784 - 1835) shipbuilding business on Broad Creek flourished with America’s

merchant fleet more than doubling between 1793 and 1805 and tripling by 1810.

His son Thurmer Hoggard IV (1819-1902) was famous for saving Old Donation

Church. In 1882 he came to rescue it by holding annual pilgrimages to the open

shell of the abandoned and burned out church so the county could not take

possession of the land.

Not until the dawn of the twenty-first century did Old

Donation see a second Golden Age and a bright forecast for the future.